a

Introduction to React

We will now start getting familiar with probably the most important topic of this course, namely the React-library. Let's start off with making a simple React application as well as getting to know the core concepts of React.

The easiest way to get started by far is using a tool called create-react-app. It is possible (but not necessary) to install create-react-app on your machine if the npm tool that was installed along with Node has a version number of at least 5.3.

Let's create an application called part1 and navigate to its directory.

$ npx create-react-app part1

$ cd part1Every command, here and in the future, starting with the character $ is typed into a terminal prompt, aka the command-line. The character $ is not to be typed out because it represents the prompt.

The application is run as follows

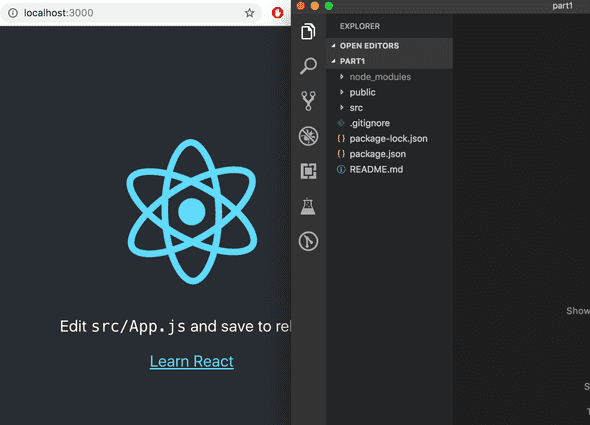

$ npm startBy default, the application runs in localhost port 3000 with the address http://localhost:3000

Chrome should launch automatically. Open the browser console immediately. Also open a text editor so that you can view the code as well as the web-page at the same time on the screen:

The code of the application resides in the src folder. Let's simplify the default code such that the contents of the file index.js look like:

import React from 'react'

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom'

const App = () => (

<div>

<p>Hello world</p>

</div>

)

ReactDOM.render(<App />, document.getElementById('root'))The files App.js, App.css, App.test.js, logo.svg, setupTests.js and serviceWorker.js may be deleted as they are not needed in our application right now.

Component

The file index.js now defines a React-component with the name App and the command on the final line

ReactDOM.render(<App />, document.getElementById('root'))renders its contents into the div-element, defined in the file public/index.html, having the id value 'root'.

By default, the file public/index.html is empty. You can try adding some HTML into the file. However, when using React, all content that needs to be rendered is usually defined as React components.

Let's take a closer look at the code defining the component:

const App = () => (

<div>

<p>Hello world</p>

</div>

)As you probably guessed, the component will be rendered as a div-tag, which wraps a p-tag containing the text Hello world.

Technically the component is defined as a JavaScript function. The following is a function (which does not receive any parameters):

() => (

<div>

<p>Hello world</p>

</div>

)The function is then assigned to a constant variable App:

const App = ...There are a few ways to define functions in JavaScript. Here we will use arrow functions, which are described in a newer version of JavaScript known as ECMAScript 6, also called ES6.

Because the function consists of only a single expression we have used a shorthand, which represents this piece of code:

const App = () => {

return (

<div>

<p>Hello world</p>

</div>

)

}In other words, the function returns the value of the expression.

The function defining the component may contain any kind of JavaScript code. Modify your component to be as follows and observe what happens in the console:

const App = () => {

console.log('Hello from component')

return (

<div>

<p>Hello world</p>

</div>

)

}It is also possible to render dynamic content inside of a component.

Modify the component as follows:

const App = () => {

const now = new Date()

const a = 10

const b = 20

return (

<div>

<p>Hello world, it is {now.toString()}</p>

<p>

{a} plus {b} is {a + b}

</p>

</div>

)

}Any JavaScript code within the curly braces is evaluated and the result of this evaluation is embedded into the defined place in the HTML produced by the component.

JSX

It seems like React components are returning HTML markup. However, this is not the case. The layout of React components is mostly written using JSX. Although JSX looks like HTML, we are actually dealing with a way to write JavaScript. Under the hood, JSX returned by React components is compiled into JavaScript.

After compiling, our application looks like this:

import React from 'react'

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom'

const App = () => {

const now = new Date()

const a = 10

const b = 20

return React.createElement(

'div',

null,

React.createElement(

'p', null, 'Hello world, it is ', now.toString()

),

React.createElement(

'p', null, a, ' plus ', b, ' is ', a + b

)

)

}

ReactDOM.render(

React.createElement(App, null),

document.getElementById('root')

)The compiling is handled by Babel. Projects created with create-react-app are configured to compile automatically. We will learn more about this topic in part 7 of this course.

It is also possible to write React as "pure JavaScript" without using JSX. Although, nobody with a sound mind would actually do so.

In practice, JSX is much like HTML with the distinction that with JSX you can easily embed dynamic content by writing appropriate JavaScript within curly braces. The idea of JSX is quite similar to many templating languages, such as Thymeleaf used along Java Spring, which are used on servers.

JSX is "XML-like", which means that every tag needs to be closed. For example, a newline is an empty element, which in HTML can be written as follows:

<br>but when writing JSX, the tag needs to be closed:

<br />Multiple components

Let's modify the application as follows (NB: imports at the top of the file are left out in these examples, now and in the future. They are still needed for the code to work):

const Hello = () => { return ( <div> <p>Hello world</p> </div> )}

const App = () => {

return (

<div>

<h1>Greetings</h1>

<Hello /> </div>

)

}

ReactDOM.render(<App />, document.getElementById('root'))We have defined a new component Hello and used it inside the component App. Naturally, a component can be used multiple times:

const App = () => {

return (

<div>

<h1>Greetings</h1>

<Hello />

<Hello /> <Hello /> </div>

)

}Writing components with React is easy, and by combining components, even a more complex application can be kept fairly maintainable. Indeed, a core philosophy of React is composing applications from many specialized reusable components.

Another strong convention is the idea of a root component called App at the top of the component tree of the application. Nevertheless, as we will learn in part 6, there are situations where the component App is not exactly the root, but is wrapped within an appropriate utility component.

props: passing data to components

It is possible to pass data to components using so called props.

Let's modify the component Hello as follows

const Hello = (props) => { return (

<div>

<p>Hello {props.name}</p> </div>

)

}Now the function defining the component has a parameter props. As an argument, the parameter receives an object, which has fields corresponding to all the "props" the user of the component defines.

The props are defined as follows:

const App = () => {

return (

<div>

<h1>Greetings</h1>

<Hello name="George" /> <Hello name="Daisy" /> </div>

)

}There can be an arbitrary number of props and their values can be "hard coded" strings or results of JavaScript expressions. If the value of the prop is achieved using JavaScript it must be wrapped with curly braces.

Let's modify the code so that the component Hello uses two props:

const Hello = (props) => {

return (

<div>

<p>

Hello {props.name}, you are {props.age} years old </p>

</div>

)

}

const App = () => {

const name = 'Peter' const age = 10

return (

<div>

<h1>Greetings</h1>

<Hello name="Maya" age={26 + 10} /> <Hello name={name} age={age} /> </div>

)

}The props sent by the component App are the values of the variables, the result of the evaluation of the sum expression and a regular string.

Some notes

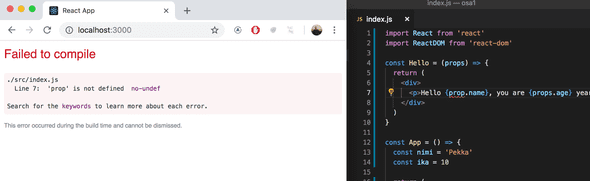

React has been configured to generate quite clear error messages. Despite this, you should, at least in the beginning, advance in very small steps and make sure that every change works as desired.

The console should always be open. If the browser reports errors, it is not advisable to continue writing more code, hoping for miracles. You should instead try to understand the cause of the error and, for example, go back to the previous working state:

It is good to remember that in React it is possible and worthwhile to write console.log() commands (which print to the console) within your code.

Also keep in mind that React component names must be capitalized. If you try defining a component as follows

const footer = () => {

return (

<div>

greeting app created by <a href="https://github.com/mluukkai">mluukkai</a>

</div>

)

}and use it like this

const App = () => {

return (

<div>

<h1>Greetings</h1>

<Hello name="Maya" age={26 + 10} />

<footer /> </div>

)

}the page is not going to display the content defined within the Footer component, and instead React only creates an empty footer element. If you change the first letter of the component name to a capital letter, then React creates a div-element defined in the Footer component, which is rendered on the page.

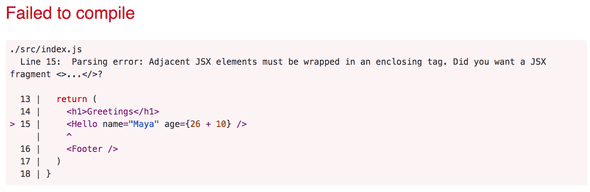

Note that the content of a React component (usually) needs to contain one root element. If we, for example, try to define the component App without the outermost div-element:

const App = () => {

return (

<h1>Greetings</h1>

<Hello name="Maya" age={26 + 10} />

<Footer />

)

}the result is an error message.

Using a root element is not the only working option. An array of components is also a valid solution:

const App = () => {

return [

<h1>Greetings</h1>,

<Hello name="Maya" age={26 + 10} />,

<Footer />

]

}However, when defining the root component of the application this is not a particularly wise thing to do, and it makes the code look a bit ugly.

Because the root element is stipulated, we have "extra" div-elements in the DOM-tree. This can be avoided by using fragments, i.e. by wrapping the elements to be returned by the component with an empty element:

const App = () => {

const name = 'Peter'

const age = 10

return (

<>

<h1>Greetings</h1>

<Hello name="Maya" age={26 + 10} />

<Hello name={name} age={age} />

<Footer />

</>

)

}It now compiles successfully, and the DOM generated by React no longer contains the extra div-element.